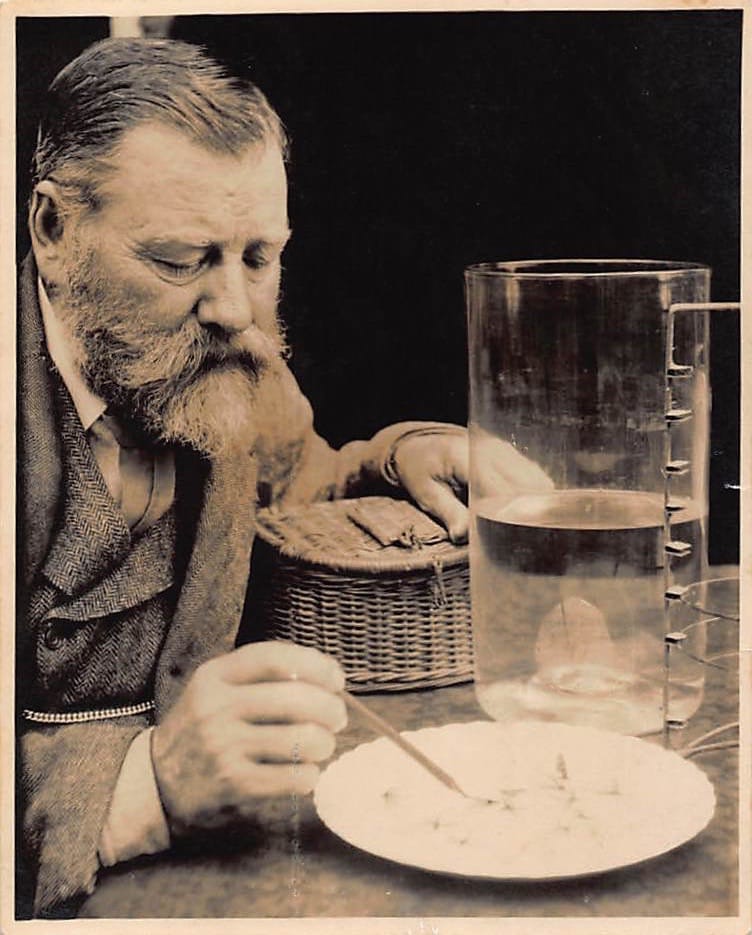

Icons: William James Lunn, River Keeper of the Test

Lunn's extensive restoration and reclamation work on the Test is a must-read for anyone interested in the practice of taking care of a river.

I just finished River Keeper: The Life Of William James Lunn, by John Waller Hills, something the Literary Fly Fisher would no doubt appreciate. Originally published in 1934, I found it at my local library, although I was the first one to check it out since 1938.

The book concerns the decades William James Lunn spent in the early 20th century as the river keeper on the famous Test in Hampshire, England, specifically at the Houghton Club in Stockbridge.

Lunn's life was certainly impressive: through perseverance and luck he escaped a life in factories, which began at age seven (!) in a brickyard working sixteen hours a day, to eventually manage the fishery for a good 45 years.

His work was extensive, and chronicled in the book. Cutting grass, and repairing banks, rearing insects to be introduced or reintroduced into the river, rearing hatchling fish, battling predators, chiefly pike. These duties are all described in detail.

For the gentlemanly type of fishing that went on (and still does) at the Test, this manicured comfort was essential. No wading, walk along the groomed lawn or path beside the river. Cast only a dry fly to feeding fish. A far cry from tactics used around the rest of the world.

The book is full of interesting anecdotes, how patterns were developed, curious rigs for breeding flies, the best food for rearing trout to be stocked (a mixture of horseflesh and mussels, actually).

One of my favorite passages is towards the end. For all its factory-work-overtones of optimization and strenuous perseverance, it's a useful approach: mix it up. And, if you're fishing with the guy who made the river and can't even catch one then, give yourself a break.

Lunn taught me what I may call imaginative concentration. It is a common mistake to say that fishing needs patience. You should be impatient, never putting up with defeat. Patience is passive: you require the active virtue of concentration: but even this must keep your inventive faculties in play. Lunn's eyes never left the water, and his mind never stopped thinking. He hated that laziness which disguises itself as activity, the energetic persistence in the use of a disregarded fly. Off with it, off with it at once, and the next too and the next until the fish either rises or removes himself. Lunn would no let me go on as I had gone on before and persevere with what I believed to be the best pattern and to persist after it had been refused. That is one way of fishing, and it often gets fish: after you have tried several likely flies, do not go on changing, but tie on the most likely, and stick with it. It is not a bad way, but it is not Lunn's way. With him as your companion, you were continually changing your fly. If all your patterns were refused he would go back to an earlier one, at which the trout had given a friendly look: anyhow he would not let you continue with the same.

You can still buy flies dressed in Lunn's particular standards today.

"William Lunn’s great-great-grandson, Ben will chronical (sic) each of the patterns the Lunns tied for their members – both those they invented as well as the classics of their peers."