Arcane specs: Fly fishing tackle measurements make no sense

Decoding the antiquated systems we inhabit in fly fishing, and measuring things, so it all matches up real nice.

I can imagine myself in the Alchemist's world, emerging from my little house in the 17th Century, forward in time, meeting a current-day angler on the river.

Oh, you like fishing? Me too! Do you prefer young, supple ash or stiffer hazel for your rods? Where do you get the stallion tail hair, from which you braid your lines? Have you got a reliable source of caterpillar gut and diamond cutters to make your silken leaders and tippet?

Wait, wait, wait. You buy your equipment at the store? It’s just…sitting there, waiting for you, not made-to-order or something you have to send away for ahead of time?

In a sport that’s rife with Ren Faire, old-world cosplay, tweed and tartan clotheshorses, where form-over-function techniques deliberately pile difficulty onto an already challenging pursuit, one would be forgiven for thinking fly fishing is just an increasingly desperate series of attempts to do anything but catch a fish.

The sport fetishizes the past, where the fish were bigger and more plentiful, hatches arrived like blizzards every day right on time, and, well, all those other things that used to happen way back when.

For the most part, this tension exists somewhere between two poles: Manufacturers wanting new anglers to buy rod setups, waders, and all manner of apparel—outwear, innerwear, underwear—and fly shops wanting newbies to buy aforementioned manufacturer gear, marked up, plus “consumables”: flies, tippet, potions and lotions to make their flies perform properly. This is the "industry". An ante in exchange for the latest fishing report, a metaphorical lift ticket every time they head to the river.

Unfortunately, at the opposite pole, there are other anglers—some, but not all—wanting the new folks to stay the fuck off the river, so they can carry on unbothered, nestled safely in the creative anachronism of an endless series of empty yesterdays.

A voice emerging from bygone days, whether a sort of Izaak Walton-era Encino Man, or an Unfrozen Caveman Angler, would bring great joy to my heart. So much is different. But so much is the same. The sport’s traditions and history force the past upon us. But they can’t secure or even suggest the future.

A Jesuit once told me, "You can't drive a Cadillac into the past." We can stick our foot in it by putting on an old pair of Red Ball rubber waders (post 'em on Poshmark for the fashionistas), or only fishing dries from Theodore Gordon’s collection. But a river is constantly running toward what's next, and cannot be stopped.

Why size matters (Or doesn't)

Starting out fly fishing, one of the most confusing things are all the arcane specifications involved in sizing. At first, it can feel like some frustrating math. Different formulas which have no bearing in present-day reality in order to balance everything out. Depending on their era of origin, this is one place our Compleat Time Traveler might feel at home. I'm here to tell you it doesn’t have to be challenging. It may even be easier when you understand the origins of these measurements.

There are three main numerical sizing patterns to understand to sizing in fly fishing:

- Rod and line weight

- Fly / hook size

- Tippet size

This simple memorization exercise comes easy to some, and is worth the effort. Pour a cup of coffee, spend ten minutes with me, and you will understand, even in your most Paleolithic form.

There is also the path of freedom and not giving a fig, and simply finding a rig, sticking with it, and letting your experience on the water guide you to new levels of understanding. Either path is totally fine, no matter what anyone else says.

I choose the path of freedom! Just tell me what to buy.

If you don't care about journeying through 25,000 beautiful years of human angling history, touching on everything from Spanish caterpillar guts to quantum mechanics, here's the tl;dr:

| If you're fishing... | Here's your setup: |

|---|---|

| ...small trout, spring creeks | 3-4 wt rod/line, 5X-6X tippet, size 12-22 flies |

| ...general trout | 5 wt rod/line, 4X-5X tippet, size 10-18 flies |

| ...big trout, streamers, wind | 6 wt rod/line, 3X-4X tippet, size 6-14 flies |

| ...bass | 7-8 wt rod/line, 1X-2X tippet, size 2-10 flies |

| ...salmon/steelhead | 7-9 wt rod/line, 0X-2X tippet, size 2-8 flies |

How did we get all these weird measurements?

Allow me another small digression about the past before we even really get started.

When I first started work in publishing at the turn of the century, I worked as an editorial clerk at a big city newspaper. At the time it was the sixth-largest newspaper in the United States. The centuries-old movable type system had been abandoned a few decades prior, and our publishing was fully digital. We used computers to write and edit copy, design pages, select images, and ultimately send them to a machine that drew all the images with a laser on a big metal plate. These plates would then be slopped (precisely) with four different-colored inks and used to print millions of pages of newsprint. These pages would be bundled up, wet and warm like newborn babes, and sent into the world. But, unlike babies, they were the most pristine at dawn, and only relevant a day or two, max. And then: To be used lining bird cages, swabbing dirty windshields in Times Square, wrapping fish. A newspaper’s lifecycle is not unlike that of a mayfly. Incubated under the right conditions for brief, fleeting glory, then rendered to a husk.

In newspaper work we used a measurement known as a pica. A pica is 12 points, there are 6 picas to the inch. Picas measure the layouts of elements on a page, box-outs and images. Column widths and heights are measure in picas. Contemporary type designers think in picas. We sketched page designs on mockups with chunky red grease pencils and drove our long metal pica rulers over heads and decks and gutters, furiously scrawling with red china markers like a general staff plans offensives. Now, when I design pages, I use pixel measurements, not picas.

Holdovers from the past

Where I’m going with this is there are holdovers from various antiquated measurement systems all around us. They have, through tradition, necessity, or sheer bull-headedness, resisted standardization. For instance: In horse racing they still use the furlong, one-eighth a mile, as a unit of distance to measure the length of a race. It comes from “furrow-long,” the length of a furrow in a farmer’s field. A rod is 16.5 feet, 4 of which make a chain, 10 square of which make an acre. It’s unclear if that’s fishing related, but size-wise, it’s certainly in the ballpark (90-foot square infield, 60’6” to the mound, outfield walls variable, orientation based on solar movement during the season).

In fly fishing, we have a group of disconnected units that all co-exist. All this draws us away from absolutes, away from the past as fixed. Insomuch as a measurement, in general, is perceived as the ultimate value judgement we can make, a deterministic certainty, it is not objective. Some units of measurement are more modern and precise than others. Anthropomorphic units (foot, palm, span) vary from person to person. Some instruments give us more detail (e.g. a laser versus a yardstick). And physicists tell us, in the world of the truly minute, we cannot measure something without altering it in some way. In an infinitely unfolding multiverse, you shoulda been here yesterday, when I caught a four-span brown on a size 24 Griffith’s Gnat and 7X tippet with a 12’ 3-weight.

But we are too poor in spirit to vacation in quantum realms, or even sharply-defined ones. Some form of resistance to certainty or absolutism is what draws the heart towards potential and possibility as zones to take our leisure. Away from the past, the already, into the infinite depth of what’s now and next. In the same way there’s no guarantee a lie that held fish yesterday will do so again today, or the fly that was lights-out this morning will again be a champion tomorrow, or even the weather will be consistent this time next week, so too does ambiguity in standardization lend an element of randomness and chance to our encounters with everyday life. It’s one of the best parts of being human.

But, for sizing fly fishing gear and optimizing your rig, some of the old school, imperial-feeling systems of measurement can be both intimidating and irritating. But you can always futz it. So here’s what you need to know.

Understanding fly fishing's arcane measurements

Like I said above, this is all stuff you should know. Is it mandatory? Not at all. Will a fish know? No. Will it impact your fishing? Yes, and spending a few minutes now will help you appreciate the sport more deeply, and make more informed choices on the water. But, you can always just ignore all this and fish. First things first:

The bigger the number, the bigger the thing: Sizing fly line and fly rods

With rods and lines the measurement is simple: The bigger the number, the bigger the thing. The rating system goes from 1, the lightest, to 14, the heaviest. This originated in fly lines, and is based on the weight of the first 30’ of line outside the rod tip.

Here’s where this gets foggy. The standard authored by the now-defunct American Fishing Tackle Manufacturer’s Association (AFTMA; now AFFTA) was meant to help ensure every 5-weight line matches every 5-weight rod. Prior to this, it was a crap shoot. Everyone used different designations for everything. "HDG" or "000" or other codenames and numbers were even harder to decipher.

The AFTMA system originated in measuring lines, but it’s more prevalent to apply to rods now, as the rod has taken its place as marketed as the more primary tool. A 10-weight rod is much larger than an 2-weight rod.

The application to practical fishing matters is simple: You don’t want a Permit rod for bluegill. It can work! But after a few weeks at the local golf course pond, one arm will look like Popeye’s. Here’s a great chart about matching rod and line to fishing situations:

Fly line weight chart

Match your line number to your rod weight. Simple! If you're measuring in grains, there's some wiggle room up or down (±).

| Line / Rod # | Application | Grains | Grams | Ounces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tiny fish | 60±6 | 3.9 | 0.14 |

| 2 | Panfish, super fine | 80±6 | 5.2 | 0.18 |

| 3 | Light trout, panfish | 100±6 | 6.5 | 0.23 |

| 4 | Spring creeks | 120±6 | 7.8 | 0.27 |

| 5 | All-around trout | 140±6 | 9.1 | 0.32 |

| 6 | Windy/streamers | 160±8 | 10.4 | 0.37 |

| 7 | Bass, shad | 185±8 | 12.0 | 0.42 |

| 8 | Light salt, carp | 210±8 | 13.6 | 0.48 |

| 9 | Salmon, steelhead | 240±10 | 15.6 | 0.55 |

| 10 | Heavier salt, permit | 280±10 | 18.1 | 0.64 |

| 11 | Tarpon, albacore | 330±12 | 21.4 | 0.75 |

| 12 | Bluewater, musky | 380±12 | 24.6 | 0.86 |

| 13 | Giant trevally / tuna | 450±15 | 29.2 | 1.03 |

| 14 | Billfish / sailfish | 500±15 | 32.4 | 1.14 |

| 15 | Marlin / shark | 550±15 | 35.6 | 1.26 |

| First 30' standard (AFTMA) | Bold = most popular for trout |

Your mileage may vary, and all bets are off when it comes to big big fish.

Of course, there’s a sticky consumerist marketing-perverted bit here. A manufacturer’s rod design choices (whether seeking performance or making cheaper rods) mean it doesn’t always work out this way. The tolerance on this measurement is not tight.

The tolerance problem (or: Why your 5-weight line and rod might not match)

Anglers have been sold the idea that casting distance is desirable. And, you can cast longer by increasing weight. So, rods get slightly heavier...and lines get slightly heavier...and pretty soon that 5 weight rod won't cast a 5 weight line from 20 years ago properly. So, designers of rods and lines make them are locked in an arms race that pushes the standards.

Leave it to Swedish rodmaker nám to embrace the ambiguity:

Noted on all nám blanks is line weight in grams and in the original AFTM system. The more people we meet around the globe the more we see that the perfect line weight for a specific rod is very individual, but we also see cultural differences. For example, in general our Swedish and Danish customers prefer lighter lines. Our Norwegian and Finish customer prefer in general heavier lines then the Swedes and Danes. This is a generalization so it’s not the truth in every case.

Most of us in nám are those typical boring Swedes whom prefer those light lines as noted above. So written on the blank is the typical Swedish light line weight and then we added a plus sign after the gram weight. The plus sign is there to explain that we see it as from this light weight and up, so it’s absolutely okey to add on how much more weight that you prefer. So, what line weight is the best line weight on our rods!? we don’t know…

Horses for courses

Where this comes to matter is in branching out to different kinds of fly fishing. If you’re just getting started, the best all-around fly rod you can own is a 9’ 5-weight fly rod. There’s a very broad range of fish you can successfully catch on this rod.

This is also a matter of evolving personal preference, and varying conditions. Typically the more experienced an angler, the greater their preference to approach fly fishing with the lightest tackle possible. I know many trout anglers who fish pretty much every situation with a 3-weight. But, if you prefer to fish streamers and you’re consistently casting in the wind, you might lean toward a 6-weight.

Wiggle room

Many have tried to rectify this situation but none of them have caught on. One, the Common Cents Initiative, tried to popularize the weight of a bag of pennies as the common measurement across rods, to more accurately describe the rod's action.

As we process our societal grief at the loss of the humble luck-bringing cent, I’ll offer a moment of silence for this effort, and its originators' well-intentioned but unsuccessful attempts to simplify this already pretty simple measurement. I leave you with their equivalency chart:

Compared to that, matching two identical integers feels pretty easy. Of all the measurements we’re talking about here, rods and lines are the simplest. And I suspect our present system is here to stay.

Over-lining and under-lining rods, to fine tune rod loading and generally cast better

Every rod, even the budget ones, has a sweet spot, where the rod will load with a certain length of a certain weight of line.

Before you buy your first nice rod, you should go to the fly shop and try it out with various lines. Weight-forward floating, full-sink, double taper. They will indulge this request without hesitation of the rod in question is in the $500 range, or you seem like a good egg. If they're unwilling to work with you, shop elsewhere.

Like I said, theoretically this is all based on the AFTMA standard and currently murkier than it was. So, practically speaking, to find the right line for your rod you might need to put a heavier (bigger number) or lighter (smaller number) line on the rod. This is called over-lining or under-lining the rod. A 5-weight rod strung with a 6-weight line is over-lined. Vice-versa when you put a 4-weight line on that same 5-weight. You got it: It’s under-lined.

The main reason you’d do this is to get the rod to cooperate. Early graphite rods, that tend to be stiffer, often like to be over-lined. Fiberglass rods, which have a slower action, do well when under-lined. A fly rod is a friend. Learning to listen to it is essential to the art of casting. Try out different lines, and let your rod tell you what it wants.

This is also variable to the type of fishing you’re doing. My 7-weight performs better with an 8-weight floating line, but loads great with a 7-weight full sink line. This is because of the relative density of those fly lines. To make a modern line float, linemakers impregnate the PVC with air bubbles. To make it sink, they mix dense metal powders, like tungsten. Your rod will respond with different types of lines, as well as line weights.

Grain weight and sizing lines to two-handed rods

This all gets ultra-specific with two-handed rods, and removable heads. Two-handed rods are typically sized with a window, in grains, detailing the lines (in grain weight) that will work best on that rod. We've got them in the chart along with grams and ounces.

Grains are most commonly in contemporary use around reloading for shooting sports, to measure gunpowder. But “grain” here does not refer to the grains of black powder. This is one of civilization’s most ancient measurements. A grain refers to the token ideal weight of a typical grain of cereal—wheat or barley. In our present-day measurements, one grain is equivalent to 65 milligrams; one pound is 7,000 grains.

I made a promise to myself I would not go to ancient Mesopotamia in this article, or the vagaries of matching up lines and two-handed rods. This is too long already. Both may be equally deep rabbit holes. Go to the fly shop for your first spey setup. But, ahh! I cannot resist leaving you with this: Another old-ass cereal-based unit, the barleycorn, is 1/3 of an inch. You use it whenever you try on shoes. The difference between consecutive shoe sizes is one barleycorn.

Here I will pause for a moment and let you collect your thoughts.

What about sizing for reels?

Reels are easy. They don’t have much of a role in this discussion beyond two factors:

- Holding the line

- Balancing the whole setup

So, you’ll have a reel that’s rated for, say, 3-6 weight lines and rods. Weight-wise, you can put any of those lines on the reel, and fish any of those sizes of rods, and the line will first both fit on the reel and balance the rod effectively. Larger lines are thicker and heavier and take up more space on the spool of the reel. Try and put a line that’s too large on, and the spool and arbor won’t have the clearance you need in order to be able to

For example: I fish a reel that’s too small on my two-handed rod, and can’t fit an entire Skagit head on it without rubbing, so I have the annoying task of dealing with a crowded spool when everything’s reeled up. It doesn’t affect performance. It’s just not stylish. Almost a flip-flops-and-socks-type situation. My friends that fish large-arbor clicker reels look at me like I’m a bozo. But, there’s a strong chance they would do that anyway, because I’m muttering aloud about how many barleycorns worth of line the reel spool holds, and how many barleycorns thick my various socks are, and if this has anything to do with the oldest ever folk song John Barleycorn and / or alcohol-induced gout or corns.

And this just confirms their suspicions.

The Backwards World of Hook Sizing

We made it out of rods and line. Sadly, it’s going to get more complex here, but just a little. And just for a minute.

There's a simple way to start this discussion: hooks and flies are sized together, the same way. When you talk about a size 12 fly, it’s tied on a size 12 hook. It always works that way. If someone tells you to tie some size 8 Green Drakes on a size 14 dry fly hook, they are asking you to engage in a snipe hunt, or refill the blinker fluid.

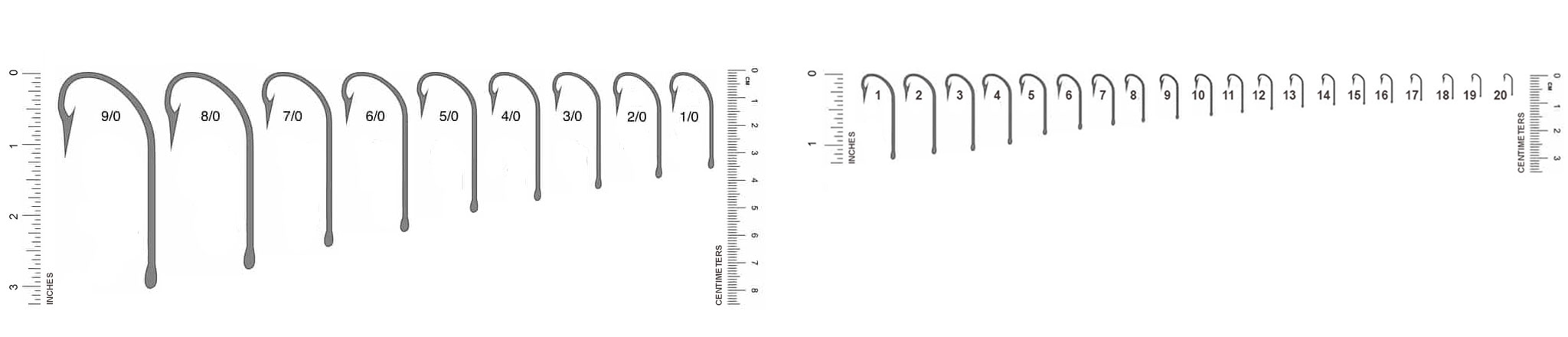

Hooks and flies are sized on an "aught" system. Imagine a number line. Put 0 in the middle. To the right, the numbers get larger, up to 28. But the hooks get smaller.

Flies/hooks we normally cast in the fly fishing world go from size one to size 22. As the number gets larger, the flies/hooks get smaller.

To the other side of the spectrum are the "aughts". Any hook / fly with /0 in its designation is BIGGER. Probably too big for a beginner to cast safely. It's easy to hook yourself, often painfully, with a hook that large.

"Aughts" go all the way to (at least) 31/0. But it's totally impossible possible to cast a hook that large with any fly rod. This is a shark hook:

Why do we size hooks this way?

Humans have been making fish hooks in some form or another for millennia. (Seriously, 23,000 years old, from shells, discovered in a cave in Japan.) But only recently (the last 200 years) did any manufacturing rigor come into play here. The history of hookmaking is pretty neat, and early steel fish hooks are prized by some contemporary steelheaders today. If you ever find any old hooks, give me a call. I'd guess the hook / fly sizing regime comes from wire gauge; at least it's presented in the same way. It doesn't matter much.

When we think about fly hook sizing, we think about two things practically:

- The fly being the right weight to cast

- Tippet being able to pass into the hook eye

If you're casting too heavy a fly on too light a tippet (1.) there's a very good chance it'll snap off. If not, the fish that will eat that large hook will break you off. In the case of 2., there's a better chance of a camel passing through the eye of a needle than a piece of 1x tippet being able to make its way into a size 22 hook eye.

Luckily, an equivalency chart works here as well. Here we go, counting down, from biggest to smallest:

| Tippet size | Hook / fly size | Tippet diameter | Breaking strength (lbs) | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0X | 1/0-4 | 0.012 | 15-15.5 | Salmon, steelhead |

| 1X | 2-6 | 0.01 | 13-13.5 | Bonefish, redfish, permit |

| 2X | 6-10 | 0.009 | 10-11.5 | Bass, largemouth and smallmouth |

| 3X | 10-14 | 0.008 | 8.25 | Bass and large trout |

| 4X | 12-16 | 0.007 | 6-6.4 | Trout |

| 5X | 14-18 | 0.006 | 4.75-5 | Trout and panfish |

| 6X | 16-22 | 0.005 | 3.4-3.5 | Trout and panfish |

| 7X | 20-26 | 0.004 | 2.4-2.5 | Trout and panfish |

| 8X | 24-28 | 0.003 | 1.5-1.75 | Trout and panfish |

Oh hey, that first column, Tippet size, is our last stop on this journey.

The bigger the number, the smaller the thing: tippet

To make the confusion all the more complete, we wind up here. The higher the number in tippet size (0-8X) the smaller the tippet.

Blame that on the stuff in a caterpillar's stomach, drawn across a diamond cutter. From an article entitled "The Mystery of the "X" in Your Tippet" by Jim Smoragiewicz of the Black Hills Fly Fishers, SD:

For some time early in the century, leaders were tied out of a silk strand that came from a caterpillar in Spain. The caterpillars were killed and then processed in chemicals to toughen their silk sacks. The silk sacks or "gut" were then removed from the caterpillar (usually two caterpillars). This packet of silk was then stretched out, usually reaching a length of 12 to 15 in. Lengths of silk longer than this were scarce, and brought a premium price.

The silk strands were uneven in diameter and needed to be uniform in diameter for use in building the leader. The way this evening process was accomplished was by using diamonds to cut one side to form a cutting edge on the hole. The silk strand was then soaked in a solution to soften it, and then drawn through the hole in the diamond with all excess silk being cut away.

This uniform piece of "silk cat gut" (gut from a caterpillar, and not a house cat) was considered to be 1X in size because it had been drawn through a diamond one time or 1X. Next, it was drawn through a diamond with a smaller hole to reduce the diameter even further. This piece of silk was now a 2X, or was drawn through diamonds 2 times. This was continued until a 5X tippet was reached, the smallest most fly fishers felt was usable at the time.

Now, if that doesn't bake your noodle. Now it's just spit out of the extruding machine.

An easy rule-of-thumb to match fly size to tippet size is to divide the fly size by 3 to get the tippet size. So, a size 18 fly should be on 6X. A size 12, 4X, etc.

Modern tippet: The debates continue

Debates rage about tippet. Whether we need half-sizes. Whether we even need any tippet finer than 3X.

Here's another ambiguity: manufacturers' X designation does not always match the tensile strength. It is not standardized across diameters. Brands are not equivalent. Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.

There is constant testing happening to find the strongest tippet of a weight class, or diameter. I strongly recommend you read this entire article on the International Game Fish Association's world record testing protocol.

Still not sure what to use? Follow this path.

Here's a fun little ASCII decision tree to help you.

What are you trying to figure out?

│

│

├─→ "I have a rod and need to match it to a line."

│ │

│ └─→ Look near the grip for weight rating (e.g., "5 WT")

│ └─→ Get one with the same number (5-weight line, 5-weight rod)

│ │

│ └─→ Rod won't load/feels wrong?

│ ├─→ Feels too stiff → size up (over-line)

│ └─→ Feels too noodly → sized down (under-line)

│

├─→ "What tippet do I need to put on?"

│ │

│ └─→ Quick rule: Fly size ÷ 3 = Tippet X-rating

│ │

│ ├─→ Size 12 fly → 12÷3 = 4X tippet

│ ├─→ Size 18 fly → 18÷3 = 6X tippet

│ └─→ Size 6 fly → 6÷3 = 2X tippet

│ │

│ └─→ OR use the general fly size overlap:

│ ├─→ 4X = fly sizes 12-16

│ ├─→ 5X = fly sizes 14-18

│ └─→ 6X = fly sizes 16-22

│

└─→"What size flies should I use?"

│

├─→ What bugs are you you seeing?

│ ├─→ Big mayflies/caddis → sizes 10-14

│ ├─→ Medium mayflies → sizes 14-18

│ └─→ Tiny midges → sizes 20-24

│

└─→ Not matching a hatch?

├─→ Streamers (baitfish) → sizes 2-8

├─→ Attractor dries → sizes 10-16

└─→ General nymphs → sizes 12-18The final showdown: Fly tying thread standards

If all this intrigues you, come with me, on into fly tying, where thread standards are even more divergent. If it frightens and confounds you, just stop now.

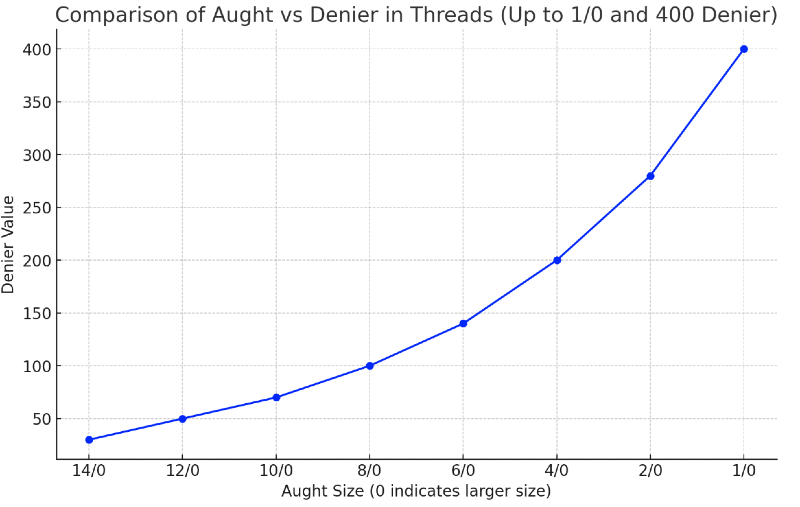

In fly tying, the "aught" system comes from surgical sutures. And everything we've already learned comes apart at the seams. The more aughts—the higher the aught number—the smaller the thread. This is opposite of how aughts are used in hooks. AHH!!! It's all (not) making sense now.

In fly tying threads, you also have to deal with denier, a garment industry standard. Some fly tying thread companies use denier, some use the aught system. And, amazingly, unlike tippet, denier doesn't mean anything about tensile or breaking strength, winding strength, or how it's braided. Denier is gram weight per 9000 yards. That's it, just weight. The GOAT king of all things tying, Charlie Craven, writes in detail here, in Fly Fisherman, about all the nuances of thread, including composition, treatments, etc.

Summing up: An eternal golden braid

“If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch," Carl Sagan once said, "You must first invent the universe.” So too go our measurements. If we were to try to wipe the slate clean and start all over again, we'd have to erase this entire universe of history.

Knowing where these arcane specifications and esoteric units originated helps me treasure the present of the sport, and dip into the past, mentally, in a way that doesn't require me to wash and hang dry my silk fly line after every session.

Of course, as I mentioned before, none of it really matters to the fish. So it's easy to go either way. I'm always happy to go the extra furlong. What about you? Share it in the comments!