Hold on loosely

Trying to not try so hard.

There's a...well...I'm not sure what to call it. A thing...that's relevant and connected to fly fishing as a way of being. Well, it's in the name, I guess. It's a Technique. Alexander Technique.

There are hundreds, maybe thousands, of practitioners and teachers of this technique around the world. And I'm sure there are an awful lot of technical ways of explaining it, that I'll be getting wrong. But here's my best shot.

Alexander Technique is primarily a posture-based kinesthetic practice, a relative of yoga and breath work. It's a practice of conscious carriage. (Carriage in how you carry yourself. Not a woke wagon.) It postulates how you carry yourself translates into your state of being in the world, health, mental awareness, and a lot more.

A lot of it is esoteric, and above my head. I'm not pretending to be an expert, or adherent, or even fully aware. I'm not on the woke wagon yet. But some of what I read has stuck with me, and is simple:

- Lengthen and release.

- Feel your feet.

- Hold on loosely.

Let's start there.

Balance and the barbell

One day, once I have truly made fly fishing a much bigger part of my life, I hope it can be my primary form of exercise, an everyday practice. Or at least a whenever-I-want practice. (You didn't think that was just an imperative for you, did you? One aim of this project is for me to ascend. For us to do it together.)

By then, I will be older, and the impact of running a boat, throwing flies all day, scrambling around, and maybe even tussling with fish every once and again will probably be enough to account for my exercise. Plus some stretching. Now, though, most of my exercise happens in a facility. More specifically, I train with an olympic weightlifting team.

Of all the fitness modalities I've tried, olympic weightlifting is the most appealing. I can see myself doing it, and learning, and maybe even getting better at it for a few more decades at least. Lord willing and the creek don't rise.

Weightlifting is an effective stress-reliever, and leaves me feeling whole after a session. And it requires a level of mind-body connection—and conscious disconnection—that does not come easy to me. To have a great session on the platform, I have to be out of my head. I have to bring forward the part of my mind that has been trained to execute the snatch or the clean and jerk at a primal level, based on consistency, repetition, and belief.

There's a paradox here. Without continuous coaching, feedback and analysis, I won't improve. But without being able to turn those aspects off when it's go time, I can't fully execute the athletic moves, access the power and velocity, necessary to get underneath a heavy barbell. It took me an embarrassing amount of time before I connected my weightlifting cues to the macro mantras I'd already learned.

- Lengthen and release. (Are your hips and chest and head at the proper angles to maintain a consistent barbell path through the pull?)

- Feel your feet. (Are you connected enough to the ground to be able to generate enough force across your entire foot to channel the power needed in the correct phases of the lift?)

- Hold on loosely. (Is your hook grip light enough that you're able to turn over the barbell quickly, not wasting precious microseconds under tension, yet secure enough to catch two-hundred-some pounds of flying gym equipment while squatted underneath it?)

One of the great awakenings of weightlifting, for me, has been that the stronger I get, the less tightly I need to hold onto the barbell. The power is there. It's the mythical "third pull" of the snatch, where you pull yourself under the barbell and catch it in an overhead squat, at full depth, that's challenging.

If I think too hard about it, and try to reason with the fact that I'm pulling down on a barbell frequently heavier than me as I'm squatting below it, having basically traded places with it milliseconds before, having propelled it from where it was perfectly, peacefully resting in gravity's cradle on the platform, to this perilous position, well, there's a chance things might not go as envisioned.

Towards deftness

Years ago, I had a boss, who was—and still is—a very large man. He's no longer my boss, but his stature remains. Not quite NFL large, but close. Pre-Millennial McDonald's Super Sized Value Meal large. Burly. Big and tall.

I was in his home once, talking with his wife, when she confided in me, almost apropos of nothing, "He's very hard on things." At first I wasn't sure if it was a work-related warning. Would he be hard on me? (No.) I realized she meant objects. He had just sat down on a bench in their foyer to put on his shoes.

The way she said it was slightly sad, as if feeling sorry for the bench and door and sweater spirits that would suffer strains and torments and early retirement through their ill-fated connection to this lumbering, lovable man.

Here it is, the very definition of "heavy handed". I've felt that way, too. Clumsy. Oafish. Klutzy. All vibrant words used to describe an imperfect way of being in the world, a just-born-ness, the knock-kneed fawn versus her graceful mother. I've felt it most when I first started using a fly rod. Bambi on ice. All thumbs, tangles, and tips.

Words are funny this way. The opposite of heavy-handedness are qualities of grace. We sometimes say someone has a "deft touch," or is deft in their movements, or dealings. Deft is a peculiar word, due to its etymological closeness with "daft" or "daffy"—crazy. Out of one's head.

In the same way "nice" had etymological origins parallel to "stupid" (truly) when we look back we realize there was something counter-cultural in qualities we've come to admire in our more refined civilization. In the dark ages, when words were what they used to be, and had yet to become what they are, to be daft or deft might have meant prancing and creeping, a fool's movements, going about the world in a tentative, unaware, naive way. Versus the burly swagger befitting the rough-hewn life of a serf, with hard hands, muddy boots, and little hope beyond drudgery, disease, and death.

The point is to not try

By now, the little alarm is going off on my head. It says "Nick, get to the point. Your attempts at deftness probably seem daft to your cherished reader. What does this have to do with fly fishing? That's what these good people came for."

If you haven't figured it out yet, fly fishing as a thing of doing, and a way of being, is all about cultivating this deftness. You start as a clumsy oaf and arrive at it through skill, and practice, and experience. But you can also get there through a mindset, and way of thinking, then not thinking.

When we step through the run, or wade up the stream, or walk the bank, it is never good to be heavy-footed. Yes, when we need a strong platform to cast, we need both feet planted. But the nimble wader, the careful, cautious stepper, disturbs fewer objects, and spooks fewer fish, and swims less frequently.

If I could have one fly fishing superpower, it would not be a laser-sharp cast, or a perfect hookset, or X-ray fish vision. It would be invisibility and weightlessness, to move through the landscape without making a dent on other creatures' consciousnesses, nary a print in the mud or break in the laminar flow.

If I could have one fly fishing superpower, it would not be a laser-sharp cast, or a perfect hookset, or X-ray fish vision. It would be invisibility and weightlessness, to move through the landscape without making a dent on other creatures' consciousnesses, nary a print in the mud or break in the laminar flow.

Prancing towards Bethlehem

Our equipment doesn't always push us towards deftness. Most fly fishing gear descriptions tout burly, bomber tacticool stuff, more at home with the SWAT team. We need to be able to walk 47 miles of barbed wire, use a cobra snake for a necktie, and live in a brand-new house by the roadside made of rattlesnake hide. Who do you love? Cordura, rip-stop, thick, waxed canvas.

Our jackets are festooned with buckles and clips and rare earth magnets and enough carabiners to belay a Prius from our molle-panelled trucks. We wear boots marketed as a "foot tractor". (Seriously, who at Patagonia thought creating the metaphor of using a tractor to plow though a riverbed was a good idea?)

What if we adopted the ultralight ethos of through-hikers and fast alpine ascenders in our gear, and accepted rips as consequences to be patched?

Tacticool is in. But, what if it wasn't? What if we adopted the ultralight ethos of through-hikers and fast alpine ascenders in our gear, and accepted rips as consequences to be patched? What if we floated in gossamer gowns, and stepped in sprightly slippers, the soul of deftness? What if our fly boxes were paper, and our flies as transitory as the insects they imitate, not a temporarily-composed lump of soon-to-be microplastics? Part of me wants that ultralight ghillie suit so I can creep around the riverbank like the Predator, and enjoys the new fly fishing fashion headed in that direction.

- Lengthen and release.

- Feel your feet.

- Hold on loosely.

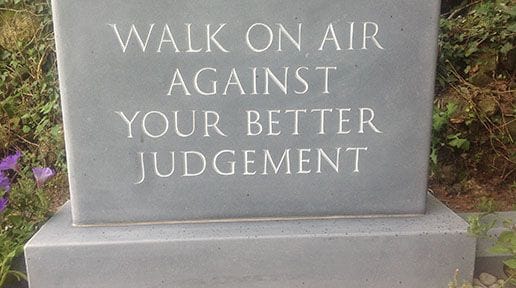

As Seamus Heaney's epitaph reminds us, "Walk on air against your better judgement."

Waving a wand

Whether or not I get a gossamer cloak and step about from rock to rock like a mad grasshopper, one place this is immediately and fairly applicable is in casting a fly rod. Hemingway fished a Fairy, don't forget. It always strikes me as so ironic that our gear is so hard, but our rods and lines are so soft, and require a light touch to activate properly.

Just like in olympic weightlifting, I don't consider casting mastery in strength or power, but consistency and economy of movement. If you ask John Juracek, who has forgotten more about casting a fly rod than most of us know, he'll tell you: "One of the most difficult things to do in all of fly fishing is to cast twenty feet." Power, strength, speed: Those are nothing without form and balance.

It's hard to convince beginning casters—especially men—that throwing it hard does not mean throwing it far. "Softer and slower" is almost always a cue I deploy in our early class days at the casting pond. Many times, as I do the rounds, knuckles will be white, hands will be hurting, and I'll have to remind beginning casters again and again to loosen up. (That, along with wrists, and stopping, remain the biggest beginner cues.) We can make the cast holding the rod with two fingers. Even the most powerful hundred-foot two-handed casts can be loosened up.

On the water a few weeks back with my friend Tanner, who has an exquisite two-handed cast, we were talking about the challenge of adapting the bottom hand and its pulling force to be the power generator in a spey cast (well, it was my challenge, to be fair). He demonstrated, using just two fingers on his top hand, merely using them to guide the rod on the forward stroke.

Not white-knuckling the cork grip of our sensitive instrument has other benefits, as well. It allows us to feel the rod flex through its entire length. As you progress through higher and higher quality rods, and your casting gets better, you will feel more of the rod flexing while you load it in the cast. If you're death-gripping it, this flex can't happen.

A light grip opens up another advanced maneuver—the squeeze. You can better control aspects of the critical stopping of the rod by squeezing the cork to bring extra counter-flexion into the blank. It's tough, near impossible, to turn the squeeze on and off when you're death-gripping all the time. One master casting instructor I've worked with, Mary Ann Dozer, had us use a kitchen sponge to learn to squeeze and release in the right moment of the casting motion.

The appropriate amount of effort is zero.

If you ask the Alexanderians, they'll tell you straight: The appropriate amount of effort is zero.

With input from Lao Tzu, marathoner Ryan Hall, and GOATed Olympic swimmer Katie Ledecky, Alexander Technique thinker and teacher Michael Ashcroft puts forward that idea, and the social impregnation that got us there:

There are all kinds of societal scripts in the modern age that push us in [effort] direction. All those hustle bros captured by Total Work push their grindset worldview, recapitulating the Protestant work ethic for new audiences. The influence of these cultural waters on our psychophysical wiring can’t be overstated.

These scripts team up with one of the core principles of Alexander Technique: Faulty Sensory Appreciation. When you try so hard all the time, that level of effort feels familiar and you stop noticing it. Put another way, years of overdoing mis-calibrate your senses so effort feels right and ease feels wrong. If you follow your feelings, you are guided back to that same old familiar where you’re trying too hard without even realising it.

Practiced consciously, fly fishing can be liberatory, and set us free of these constraints. We can all become buoyant, wading waist-deep in the unburdened consciousness of a no-effort experience. Unattached to outcomes, not trying hard, if at all.

We can all become buoyant, wading waist-deep in the unburdened consciousness of a no-effort experience.

We can all experience deftness right now

I was making a fried egg for my daughter the other day when I remembered a story of deftness in action, and the kind of magic that can happen when instinct meets opportunity.

My friend Colin became an avid hackeysacker (...footbag player?) in college. He went on to work as a short-order cook in a diner. (What else are you going to do with a degree in Footbag Management?) One day, between carton and griddle, an egg slipped out of his hand and headed straight for oblivion on the kitchen floor. He was able to execute a perfect stall on the top of his foot, saving the egg, then popping it back up and catching it, for style points.

This deftness is the domain of the street food vendor with the sticky ice cream, of Tom Cruise in Cocktail, of the guide who has tied so many clinch knots they can hold the loop and twirl the bug around their index finger then lube and nip the knot in their teeth, all under two seconds. Germans call it Fingerspitzengefühl, or "fingertip feel," a sort of embodied knowing and the ability to react with just the right amount of force.

We work towards deftness, in the gym, on the water, with each other. It's the undercurrent of the entire practice.

But you can be deft now, in this moment. Right where you are. I know you can be perfect, and make no effort at watching, looking, and sensing.

Take thirty seconds.

Lengthen and release.

Feel your feet.

Hold on loosely.

Then walk on air against your better judgement.

𓆟 𓆝 𓆟