Read By the River: Nature's Best Hope

Our river nerd book club turns to trees: backyard conservation, native plants, and creating habitat that supports the food web.

\For our latest Read By the River book club series we turned to Douglas Tallamy's Nature's Best Hope (2020), a compelling call-to-arms for transforming our backyard landscapes (as well as all the other airport, shopping mall, educational campus, etc. land) into more functional ecosystems. For us anglers and river fans, his message rings true, if a step adjacent. Rivers health and the abundance of aquatic life that fish depend on are inextricably linked to the terrestrial habitats surrounding our waterways, which are just outside our backyards.

The caterpillar crisis

Tallamy's central thesis revolves around a series of baffling statistic about how important insects are to birds. Here's one: 96% of North America's terrestrial bird species raise their young on insects rather than seeds. This creates an enormous demand for caterpillars, with parent birds making dozens and dozens of trips per day to feed nestlings scads of caterpillars.

Our conversation highlighted how difficult it is to spot 70 caterpillars in a single day as a human observer, yet parent birds must find this bounty consistently. Tallamy's research demonstrates the dramatic difference in insect-supporting capacity between native and non-native plants. It's something he's touched on a lot in his other books, which continue around his central thesis of more native plants, more things for birds to eat. If anything, my only knock on Nature's Best Hope is that it's pretty similar to his other books, The Nature of Oaks (2021) and Bringing Nature Home (2009). Which is OK. I consider Tallamy an activist author, and packing the same crucial argument in slightly different ways goes with the territory

Anyway, another show-stopper factoid: Oak trees can support over 280 species of moths and butterflies, while introduced species like ginkgo trees support virtually none. The Native Plant Finder provides location-specific recommendations, showing exactly how many species each plant can support in your area. I don't need to reiterate it again, but I will for the folks in the back: We're in a slow-motion insect population crisis around the world, and need to think seriously about how these keystone species can be brought back to populations that feed the world, either directly (like birds and fish eating bugs) or by pollinating our crops.

Portland's urban forest

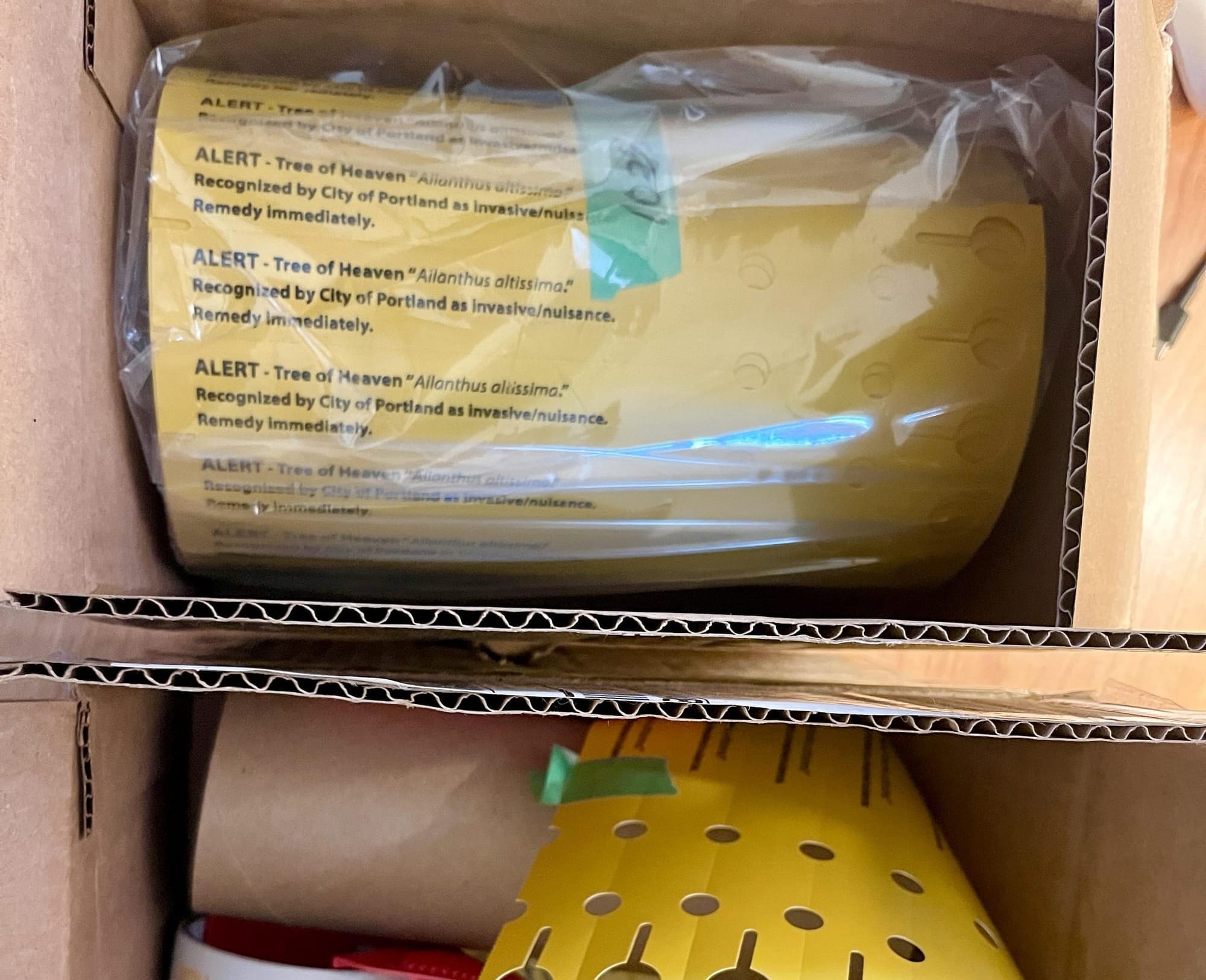

Several times in the book Tallamy mentions Portland, a green city with significant urban tree cover, being deficient in natives. Let alone the invasive species. We dug in on the Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), an aggressive invasive species going crazy wherever it's overlooked throughout Portland's neighborhoods. These fast-growing, tough-to kill trees represent everything Tallamy warns against: They support no native insects, outcompete native species, and create monocultures that contribute nothing to local food webs. Lately, though we've seen a guerrilla urban forestry campaign of sorts on the r/Portland Subreddit, with precise instructions on how to eradicate the trees, folks acting as spotters and sharing tree locations, and even tree tagging actions to raise awareness and organized activities.

The authentic (prior to colonization) ecoregion in the Portland Metro area is known as Willamette Valley Oak Savanna, which is 99.5% altered by settlement. The group wondered where we might be able to see something that felt preserved and intact. The search for authentic oak savanna experiences led to recommendations for Milo McIver State Park's disc golf course, where the fairways wind through what appears to be an intact oak woodland with natural grass understory. The Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge was mentioned for its ancient oak stands, complete with abundant galls (that you can turn into ink!). Another example of an intact oak savannah area is Bald Hill Farm, near Corvallis.

Why should anglers care about native plants?

For fly anglers, a healthy native river (riparian) zone translates directly to stream health. Riparian corridors filled with native plants create:

- Abundant terrestrial insects like ants that can feed trout

- Stable stream banks with deep root systems to stop erosion

- Appropriate canopy cover and temperature regulation (shade)

- Leaf litter that supports aquatic invertebrate communities

What's especially galling (is that an oak pun?) about the Tree of Heaven is that it's invading angling zones, it's not just confined to urban forests. Several areas on the Lower Deschutes, especially Beavertail campground, are overrun by the trees, which are surely impacting native riparian vegetation and thus insect populations.

Of course, cold, clean water is the key to healthier fish populations, and advocating for that continues to be our number one concern when it comes to long-term stream health. But, knowing what plant species have co-evolved with bugs and birds and fish for millions of years feels like an important part of the deal. The way Tallamy marvels at the relationships between host plants and their unique caterpillar and butterfly companions is the same sort of love and respect for the intricate movements of nature and evolution that anglers use when they describe the beauty of trout.

Start with the hell strip, then kill your lawn

I'm in a little bit of a transition zone, having recently (in geological time) moved from a garden I built into a platinum-level Backyard Habitat into one that's chock-a-block with Home Depot special plants. For me, our hell strip (the space between the sidewalk and the street) was the first discrete zone I could turn for some native habitat creation. We stuck some small, street-tree-approved oaks in ours, then put some ocean spray (Holodiscus discolor) as understory, hoping to create a caterpillar zone. Next, we're working back, towards the house moving to replace our lawn and some of the ornamentals with plants that'll do more for bugs and birds. Not only is it annoying to mow during fishing season, and thirsty (that water bill is creeping higher) but now I know a bunch of well-placed natives, or a grassy meadow, would do a lot to bring bird species to the yard.

Who knows where we could wind up? Doug Tallamy appeared, funny enough, in the New York Times' print edition the day we posted this story, talking about species-rich microforests. Thanks to Robert for the heads-up:

What book should we read next?

Toss us a recommendation in the form below:

For further inspiration (and hardcore botany)

Tallamy's work is a great entry-point to this fascinating area of botany thinking. If you're interested in something a little more, hmm, hardcore, I'd recommend you check out Joey Santore, a Chicago-born botany educator who's on YouTube and Instagram as Crime Pays But Botany Doesn't.

His explorations are endlessly entertaining, and as a self-taught botanist he's an inspiration for others who want to engage with scientific topics as a layperson and might not know where to start. (Hint: start in the field, by following your passion. Check out this recent Reddit AMA with Joey Santore from the Native Plant Gardening subreddit to learn more.)

This discussion was part of our ongoing Read By the River series, where we explore angling and angling-adjacent books that dive down all the various rabbit holes that fly fishing opens up. Join us for future conversations about the literature flowing through our hobby.

Previously:

𓆟 𓆝 𓆟