Swinging wet flies and soft hackles

Try out one of the most straightforward presentation styles, for both trout and steelhead

Welp, it's almost tying season. And this winter, I'm focused on the flies featured in the new Patagonia book Pheasant Tail Simplicity. So, I wanted to take a minute and round back on one of the most prevalent presentation styles in the history of fly fishing: the swung wet fly.

Lots of us get started fishing nymphs, or dry flies. In my perfect world, we'd all start with the swung wet fly, because it's simple and straightforward to understand, and doesn't ask all that much from an angler. You don't need to cast far, or even straight, to make it work. And, when you vary the size of the gear (from a tiny trout rod to a big rod for steelhead) and the size of the flies (ditto) it can be useful in any moving water situation.

There are a few flies in the book that I'd classify as soft-hackled flies fished wet: Pheasant Tail Soft Hackle, Pheasant Tail Flymph, and Pheasant Tail Jig. I'm personally particularly interested in tying some Pheasant Tail Soft Hackles; since the previous (essential) Patagonia 'how-to' fly fishing book, Simple Fly Fishing, came out, Yvon Chouinard has written about using that fly, also known as a Partridge & Pheasant Tail, in all his fly fishing, from bonefish to Atlantic salmon and steelhead. Might I catch a steelhead this season on a classic soft-hackle? There's only one way to find out.

Historical connection

Wet flies and soft hackles were probably the first kinds of flies ever developed. Or, rather, the first flies ever developed were fished wet. Here's more on that from the Comptoir General site.

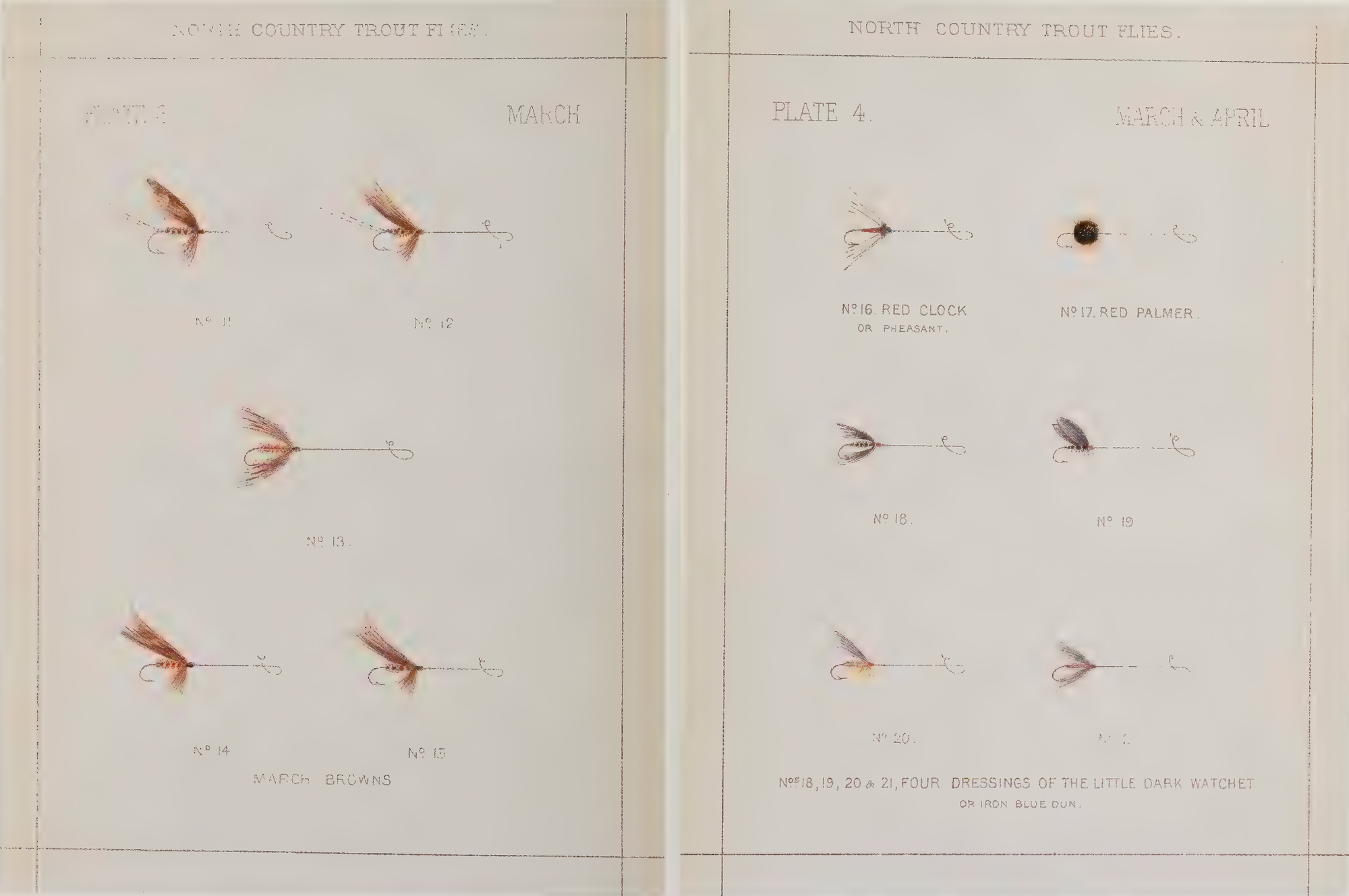

More recently (in the 19th Century) soft hackle flies were chronicled in England, and known as "North-Country" flies.

So, tapping into the wet fly can help you feel connected to two-thousand years of glorious history, from Macedonia to the Madison.

Why fly fish using wet flies

Presenting a wet fly or soft-hackled fly is one of the most time-tested, relaxing methods of fly fishing. It's at once classic and contemporary, having been a preferred method for hundreds of years. And, best of all, the skills you build fishing flies on the swing for trout can applied to steelhead using two-handed rods and heavier flies.

There's nothing I find more enjoyable than fishing upstream with a dry fly, working to find various angles of approach and suss out where fish are hiding. Then, when it's time to turn around, or I get a little frustrated and need a time-out, clipping the dry off and putting on a soft hackle, and approaching the same runs, riffles, and pools from the other direction. Another part of the reason why swinging wet flies is so fun? The fish just hook themselves. Seems suspect, but read on.

Aren't all flies wet flies?

OK, let's back up. Yes, all flies are technically wet. In that they all touch the water. That's about where the comparison ends. Here's a simplified way to think about it:

- Dry flies float on the surface

- Nymphs sink to the bottom

- Wet flies are fished somewhere in the middle.

To add a little more context, dry flies imitate insects that are on the air side of their emergence. Nymphs imitate insects that are still in their aquatic phase. Wet flies (especially soft hackles) are in between, with some imitating emerging insects, some imitating insects that failed to emerge and fly away and are thus headed back to Davy Jones' locker, some imitating swimming fish, some just being impressionistic creations not unlike cat toys, taunting salmon and steelhead to strike.

Are all wet flies soft hackles?

Here's where we get into the vast reaches of fly taxonomy.

No, not all wet flies are soft hackles. Classic Atlantic Salmon patterns, for example, are fished wet, on the swing. They don't feature much soft hackle, rather hair wings, and straight, strong feather wings.

Typically soft-hackled flies are tied with feathers from partridge, grouse, or starling skins, or similar light-feathered birds. Jays, snipe, magpies, etc. One easy way to recognize soft hackle wet flies is to go by the name that Brits call them: Spiders. The hackle wrapped around the hook's shank, near the eye, splays out into what look sort of like a spider's legs.

Presenting flies across the entire water column

One of the biggest things I've learned angling is that there are way more kinds of water contained inside water than I ever imagined. No, this time it isn't a koan.

You assume, "Hey, water, it's all water. It's uniform throughout." Not so, my good sir / madam. It's different throughout. Different temperature. Different speed. Different turbidity. Different taste and smell. The latter, very apparent for salmon finding their natal streams; less so for us.

Within the broad reaches of a river the water can really vary. And we need horses for courses, flies and tippet that can do the job. A lightly weighted soft hackle fly is going to be fished in the upper third of the water. It doesn't have the weight to get down lower.

And one place soft-hackled wet flies shine is in the surface film, the meniscus, the thin layer separating the water from whatever comes above it. Sometimes, the combination of a floating line, a relatively buoyant pattern, and some floatant is enough to keep it up top. "Fishing the Film" by Gary Borger is a book that looks at the central character the surface film plays in the life of a fish, the interface between water and air that holds the two apart, and well worth a read.

For deeper presentation: the flymph

If you need to get deeper in the water column, or are fishing in more turbulent waters, you can use a flymph. Which is a soft hackle that is tied on a heavier hook, or features a bead. Flymphs fish deeper, and are sometimes fished as nymphs. (I'm not 100% certain why it's called a flymph, that feels like a portmanteau of fly-nymph? It's a little confusing on our Venn diagram. Anyway.)

Flymphs are fished more like nymphs than soft hackles, but they still do the same thing: imitate an emerging insect. you need to impart some kind of action to move them up and down in the water column. Typically this is accomplished by making small twitches on the rod tip.

Flymphs work great when you want to fish two wet flies together. Tie a flymph on as the point fly (the last on the line) to help the whole rig get grabbed in the current. Tie an unweighted soft hackle off a dropper higher up the rig. The flymph point fly will lead the way, and the unweighted soft hackle will move free.

A few of my favorite fancier flymphs right now come from the brain of Brian Silvey: Silvey's Bead Head Prime Time Pupa (or at Slide Inn) and Silvey's Caddis Pupa. These are two great caddis imitations that give good action on the swing. I prefer the prime time right now, I like how the bead is concealed in the body of the fly.

Casting and fishing wet flies

One cool thing about wet flies and soft hackles is their versatility. You can swing the fly, basically casting it slightly downstream and letting the current pull it taut through the run, and then letting it dangle. You can cast it downstream and give it little twitches along the way, never letting it get too taught, then let it dangle. You can fish it like a dry fly.

Swinging is the simplest and most popular way to fish wet flies. It's how we swing for steelhead as well. Controlling the speed of the swing is the name of the game. Swing presentation are useful for streamers, too.

The swing

Casting a fly to swing it is dead simple. Just cast your line downstream and across at a 45-degree angle or so, and let the current carry it, making a few small adjustments—mends—to help it swing faster or slower.

You want your fly swinging like a pendulum across the current. We mend to avoid varying currents across the surface deforming the presentation—putting belly into the line. Notice that a faster current near you is putting a big hump into your line? That's the belly. and it's dragging the wet fly out of position. Flipping the line upstream will help eliminate that. Here are two simple diagrams illustrating the process from Michigan guide Ted Kraimer:

Swing angle and speed on a wet fly tend to be most important when you're steelhead fishing. Steelhead strike out of aggression and instinct, not necessarily to eat bugs. They're not necessarily seeing a food source, rather an anomaly to be terminated, or a long-ago instinctual impression of striking flies in their youth as parr. Though, opinions vary here, as the world of the steelhead is vast and mysterious.

The dangle

When you're trout fishing with an unweighted soft-hackled fly, you'll have the most likelihood of a strike at the end of the swing—known as the hang down, or the dangle. This is where the fly, gently undulating up and down, hackles flaring in the manner of an emerging insect headed for the surface, is most enticing to trout.

Arguments about how long to let the fly hang vary, but I tend to linger in the hang down. To dilly dally in the dangle, as it were. I try and give it a good 30 seconds. It's a good time for me to space out and listen to birds or feel the rocks under my feet.

This is also a great time to try one of the most fun intermediate methods of fly presentation, the Leisenring Lift. While you're in the dangle, slowly lift your rod tip, then bring it down again. The motion of lowering your rod tip will add slack to the system, the fly will drop, then rise again when it starts dragging again, a motion fish find irresistible.

When you're fishing a flymph, you're more active during the swing, as the fly moves down the run, and you're twitching your rod tip more aggressively. The current is pulling the weighted fly harder than an unweighted fly, so you've got more potential for action. Here's Patagonia's Yvon Chouinard on how to fish flymphs, from the Pheasant Tail Simplicity promo package:

Moving through the run

Swinging flies for steelhead is an orderly affair. First, you need to find the right type of water: typically a run, where the water's moving about walking speed, without much surface disruption, wide and long enough to cover a lot of it. You cast, mend, let the fly swing, take two or three steps down the river, then do it all over again.

When you're swinging soft-hackles for trout, though, there's much less need to be choosy. Swing those flies through riffles, runs or pools. Try and lengthen the amount of line you cast so you're not directly in the eye-line of the fish downstream, and saunter on downstream. Try not to run into your buddies working upstream, or fish over the pools they're headed for: Typically I move a lot faster downstream than up, maybe that's just the natural feeling of being pulled by the current.

Setting the hook

Perhaps the part that I, the angler, find the most irresistible about swinging wet flies or soft hackles is the hook set. Which, I almost always have nothing to do with.

Let's go back to our first principles of this technique. The fly is under tension through much of the presentation. Drag on the fly creates the movement that entices the fish. So, when the fish comes to pluck the fly out of the water there's a near-instant hook set. It's automatic. All of a sudden, whether it's midway through the swing, or on the hang-down: Bang, you've got a fish on. Nothing could be easier.

Like with everything else, things are a little more complex with steelhead, so I'll leave off going into detail on a steelhead hook set. Other than to say most times beginning anglers set too soon on a swung fly steelhead grab, and sometimes they don't set at all. And such are the mysteries of life.

Fishing soft hackled flies like dry flies

You can also fish wet flies—especially soft hackles—more like dry flies, casting up and across, or wherever. They won't ride up as long, but if they're dressed in floatant, they'll hang out in the surface film, oftentimes long enough for a grab.

Learn more about soft hackles

First published in 1975 and now over 50 years old, "The Soft-Hackled Fly" by Sylvester Nemes remains the best introduction to patterns and technique around fishing soft-hackles. That's where I'd suggest you start if you want to dig in even more.

Nemes wrote a lot about soft-hackled flies, and in his lifetime several books on the pursuit and the history of patterns. Nemes' papers are at Montana State University in Bozeman if you're ever interested in digging.

Tips and tricks? Favorite patterns? Let me know in the comments

𓆟 𓆝 𓆟