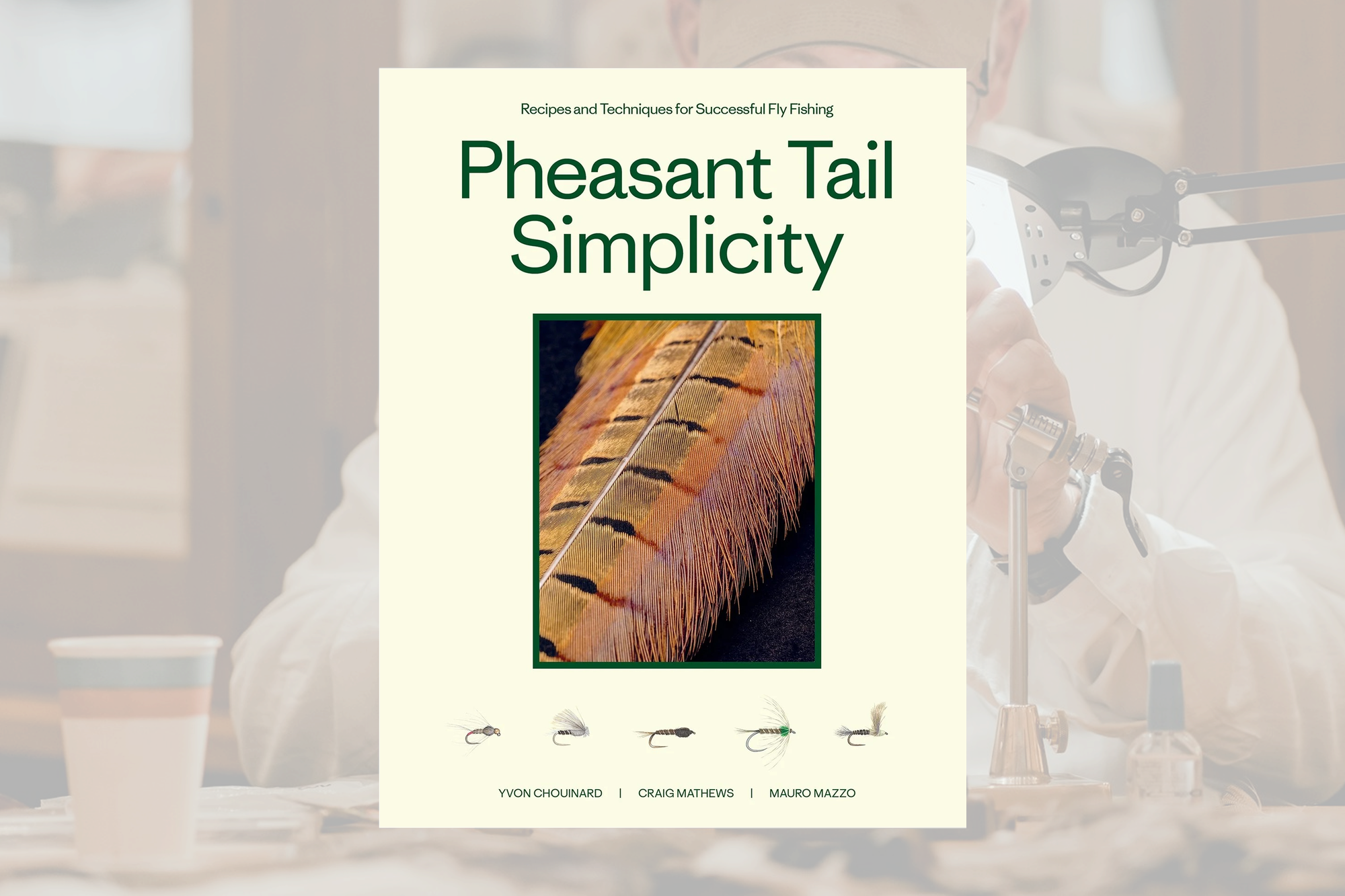

Talking Pheasant Tail Simplicity with Craig Mathews

From tenkara-wielding biker gangs to roadkill feather ghouls to Yvon Chouinard's "stroke": A conversation with fly angling icon Craig Mathews never disappoints. Hear how Pheasant Tail Simplicity is creating a new generation of fly tiers, observation as the key to angling, and much, much more.

My formative fly fishing years began when I started making annual pilgrimages to the Yellowstone area of Montana with my dad. We’d head out every August with the Michigan Fly Fishing Club, and explore the varied waters of what’s widely recognized as the fishiest area in the lower 48.

Our own personal epicenter was Blue Ribbon Flies. Of all the fly shops in West Yellowstone it felt the most sophisticated, and had the most fully-formed perspective—dare I say philosophy—on how to fish the region, at the very least, and maybe even the while world. The fishing report handwritten on BRF's door tempted anglers with zen koans. And inside awaited a veritable pleasure palace of all things fly fishing. And, above all else, it was owned by a guy who came from Michigan himself and figured it all out.

For a novice like me, one of the most exciting revelations was that Craig Mathews—Blue Ribbon's co-owner, the guy who wrote the books I’d studied before the trips, who fished in the DVDs I watched, who wrote the catalogs I waited for every November—was just sitting right there in the shop. There he was: Tying flies and shooting the breeze with customers. You could just come in and talk with him.

Craig, along with his co-owner John Juracek, and the whole crew were happy to engage and share what they knew. And as we learned more, and ventured beyond the rivers and lakes in all the popular books, we’d get more sly winks and nods and knowing looks from the gang. Their looks told us we were progressing in the right direction, advancing beyond, into the heart of the last best place. And the cryptic advice on the outside board started to make more sense.

Fly shop employees sometimes have a reputation as standoffish and obtuse. "Fishing’s good, go anywhere"-type terse, one-note answers are not uncommon. Not at Blue Ribbon. We we conscious of not abusing the system, but more often than not a trip to the shop would result in a long conversation about anything and everything related to fly fishing, and a cup of flies that were effective in the region, and at home.

Fast forward to today, some years later. Part of the reason I'm so excited about Pheasant Tail Simplicity is because I’ve wondered a lot about how to pay forward the knowledge I was given. And now, conveniently enough, a lot of it has been packaged up for anyone to use, anywhere.

Craig and his co-authors, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard and renowned Italian nymph angler Mauro Mazzo have continued to drill the vein they first mined in Simple Fly Fishing. Namely, this sport doesn't need to be so complicated. It's a theme not unlike famed designer Dieter Rams': Less, but better. Now, they're applying this perspective to fly selection and fishing technique.

Last week, Craig and I connected at the tail end of his press tour for the book, as elk season and the bird dogs beckon. A few years out of ownership of Blue Ribbon, Craig remains a paragon of ambassadorship for the sport.

Our wide-ranging chat touches on the book and the flies in it, but also the satisfaction one can find in the sport, and the energy he’s getting from the next generation of fly-tiers and stewards rising to guide the sport's direction. Not to mention all his hilarious stories.

What follows is a lightly-edited transcript, but members can access a recording of our whole conversation, including banter about the weather, Michigan, and more. It’s worth a play, to hear the passion and enthusiasm Craig exudes, but you can also find his warm smile and great storyteller's mien in any of the videos Patagonia produced to go along with the book.

Areas we touched on:

- Pheasant Tail Simplicity, the book

- Wisdom for beginning anglers

- Collaboration and creative practice

- The future, activism, and advocacy

Pheasant Tail Simplicity, the book

CFS: What has the reception been to the book so far?

CM: Oh, it's been amazing. Of course, there's been a lot of really great publicity about the book, and we hit the bricks when Yvon came here a couple weeks ago to do the kickoff event at MSU—Montana State University—I went to the other MSU. And then we went to the Dillon store, and there was a huge, huge showing at both events.

What really tickled me are the number of young people and beginning fly tiers that showed up with great questions at both events. And that's the future, of course, of the sport. And not only young people, but a fair amount of older folks that said, "You know what, we're gonna give it a shot. We're gonna try to tie these simple patterns." So with that, I think we'll be doing some fly tying shows here pretty quick, trying to get some beginners into tying flies.

CFS: Do you have a favorite fly in the book to tie?

CM: There's two flies I really enjoy tying. Number one is the Sparkle Dun. That's been our signature fly. John Juracek, our former partner in Blue Ribbon Flies, he and I came up with that pattern, God...almost 50 years ago now. And the X Caddis, that my wife, Jackie, designed, shortly after we came up with the Sparkle Dun, that imitates, of course, mayflies.

CFS: I was wondering to myself, "How many Sparkle Duns has Craig tied?" Do you have a sense of that number?

CM: I could go back. I keep track of every fly I tie. And now, I tie for myself, and I tie for some friends, and I tie to donate flies to fly fishing clubs. I don't tie for bucks anymore. I do it for the love of it. I still tie about 700 dozen flies, say 800 dozen flies a year. At one time, I was up to 1,500 to 1,800 dozen a year. And I could tell you, if I went back in all my records, I probably could add that up, but it's certainly thousands of dozens of Sparkle Duns.

Watch Craig tie one of the tens of thousands of Sparkle Duns he's twisted up.

CFS: Is this a paper log? How do you keep track of all this?

CM: Yeah, it's all paper, it's all hard copy. Most of my journals and whatnot I've donated to Montana State University Libraries, but I've kept my fly tying and fishing journals. I guess when I pass away, they will go to Montana State University, but for right now, they're here at home.

At one time, I was up to 1,500 to 1,800 dozen a year.

We're gonna have Nick Lyons out next summer. He wants to come out one more time—he's 93 years old—and we're gonna spend some time with Nick in the park, as well as just visiting and talking about our past fishing experiences on the creeks.

The philosophy behind the book

CFS: The patterns in the book are patterns that you innovated, that you and John and Jackie all were field testing decades ago. But at the same time, nothing in the book feels like old stuff in a new package. There's something about it that's exciting and dynamic and fresh. What do you think that is, that sort of special sauce or magic dust that's on this, that has that all feeling so fresh and new?

CM: Of course, there’s some of the new stuff that Yvon and Mauro both came up with as well. But when we decided, and how we decided to write this book, there were so many patterns over the years that I had been fishing personally, using pheasant tail. And I was thinking these flies would never resonate with many of the fly fishing customers. In other words, we probably couldn't sell them because they're so simple. And they imitate, of course, insect behavior and what triggers trout's reaction to them very well. We just started introducing them and started leaking some of the information out to other fly fishermen, and found that they really worked well in most fly fishing situations, and solving many of the puzzles, if you will, of dry fly fishing.

Because, let's face it, pheasant tail is so easy to come by. It's inexpensive, it's easy to use. A lot of people have trouble with dubbing, and now, simply, they just wrap a couple of pheasant tail fibers on and replace dubbing. So with that, you know, it really gains some traction among some of the people, some of the old experienced fly tiers, if you will, who are like myself. They tie simple flies because they want to go fishing. They don't want to sit there and spend all this time tying flies that really look more like a '56 Buick convertible with all the sparkle and glitter. And fish have become educated, and they refuse those patterns.

They tie simple flies because they want to go fishing.

So, with that, we decided to really simplify things and imitate what triggers trout; what trout recognize as food and the behavior that they recognize. Yvon likes to use a little bit of action to his fly. I do, too, in some of my caddis patterns. And that's how we kind of came up with these series of pheasant-tailed flies.

At left: a Sparkle Dun; right: an Iris Caddis, both Blue Ribbon specialties featured in Pheasant Tail Simplicity | 📷 ©Tim Davis, courtesy Patagonia

Minimalism and running a fly shop

CFS: One of the first clichés you learn in fly fishing is that the fly catches the angler before it catches the fish, which is why we have those '56 Buicks. Do you think it would have been hard to have this sort of message of minimalism, of you only need a select few patterns, when you still owned a shop? Would it have been as easy to go ultra-minimal when you had to move flies every year?

CM: I think about that from time to time. Here we sat, and we had a hundred and some feet of fly bins, with thousands of different fly patterns, many of them incorporating a lot of flash, a lot of beads and that sort of thing.

But when it came down to it, why we decided to write this book, is because we're sitting there with these vests that so packed with fly boxes you could barely move around. But yet, we had, in the upper left-hand corner, in that tiny little vest pocket, we had a little plastic hook box with about five or six different patterns, and that's all we ever used.

And Yvon, Mauro, and I are sitting there one day on the bank of the river here, taking a break, and we're talking about it, and we all had that secret little fly box that we carried that had the most effective fly patterns. And I often thought of that at the shop, too, way back when. I'd sit with guys, and we'd circle the fly patterns. They wanted me to pick out a selection of flies that were gonna work in Yellowstone country while they were here, and I'd sit there with this cup, and I'd have a couple Sparkle Duns, a couple Iris Caddis, a couple X Caddis, and a Zelon Midge, and I'd say, this is all you need.

And they'd look at you, and they'd go, "Wait a minute." I had guys literally follow me around and start stuffing, sometimes over $1,000 worth of flies in a little cup. And I said, you don't need all those flies. And they said, "Well, how can you stay in business selling flies, and you're trying to talk me out of all those flies?" And it was really cool, because they'd end up buying, rather than 50 dozen sparkly ineffective patterns, they'd buy 50 dozen Sparkle Duns and Zelon Midges and that sort of thing. That worked. And I think that really helped build our business, because it certainly added credibility to our reputation.

CFS: I was in a couple of fly shops in Ennis, where the hopper row was like a candy shop with every single possible shade of pastel, and it's like, how do you choose? "Oh, let's tie on a baby blue one, and now let's go to a peach one, and now let's go to a bright green and dark green." Even on the Madison, that seems like overkill.

CM: You know, for the most part, color doesn't matter all that much. There are times, and I write my introductory section in our Pheasant Tail Simplicity book, where color did matter, and one time on Spring Creek here with Nick—the creek that Nick immortalized, the iconic Spring Creek here in the Madison Valley. Where the fish are extremely selective, and color at times can make a difference. But for the most part, walk into a fly shop, and you can attest to that, because there's 50 different colors of hoppers, 20 different colors of ants—have you ever seen a chartreuse ant? So color really doesn't matter all that much.

Have you ever seen a chartreuse ant?...Color doesn't really matter all that much.

Are you just getting going fly tying? Feeling a little intimidated? Give these Six Tips to Start from Craig a look, to get your confidence and approach squared away.

Wisdom for beginning anglers

CFS: In the same way you've shed layers of flies in terms of your wisdom when you think about your own angling, what do you wish you knew when you were just starting out that is important for beginning anglers to understand?

CM: Focus and patience and observation. A lot of guys get to the river and there's nothing going on because they're not there at the right time. And there's so much literature on when to be on the river, when you have dry fly fishing. I'm sitting on one little piece of water. And I'm waiting. Again, I like to fish dry flies, so I sit on one little piece of water at a time when I know there's going to be surface activity. I sit and I focus on a particular piece of water, and I do exactly what the river tells you to do. Every piece of water reads like an open book.

Every piece of water reads like an open book.

And if I want to fish midges right now, I'll take the bird dogs and run the bird dogs all day long, and I'll be on the river at six o'clock at night, and I'll have an hour and a half of incredible dry fly fishing during midge times. Most guys fish from noon to three during the comfortable time of the day, but this time of year, really, nothing's going on at that time period unless you have inclement weather, you know, rain, snow, and then you have good Baetis emergences. So by knowing when to be on the river and knowing what to focus on, looking for rise forms and recognizing rise forms, and patience. Not just grabbing a fly rod, putting on two bobbers and two nymphs, and mindlessly working up the bank 100 miles an hour.

I had a classic example, the other day. I was fishing $3 Bridge, it was snowing, fish were rising like crazy to Baetis about 3:30 in the afternoon. And a guy comes up behind me, and he's got a streamer on bigger than most trout that he was catching, this big black streamer. I said, "How you doing?" He said, "I haven't caught one yet, but I think I'm gonna catch one before dark." He said, "How you doing?" "I said, "Well, I caught three or four fish sitting here." There were fish rising. And I said, "Have you seen any rising fish today?" "Haven't seen a one." And they were rising right on the end of his fly rod. He failed to notice those fish rising. And again, just observation, patience, and doing what the river tells you to do.

Simplicity across species

CFS: One of the parts about the book that I love the most is the idea that a pheasant tail, a pheasant tail soft hackle, or some variation thereof, has caught grilse, has caught steelhead, has caught Atlantic salmon, has caught bonefish. You've fished all over the world. For beginning anglers, or less experienced anglers, how does this message of simplicity expand as anglers try to vary their repertoire and find kind of what niche they fit in? Like, are they a steelheader? Are they a trout angler? Are they a marine angler looking for saltwater stuff? How can they kind of maintain a level head around what the universal kind of ideas are in the sport as they experiment in those places?

Send more time, again, focusing and on patient observation, rather than just going in and buying a bunch of flies and tying them on and frothing the water with them.

CM: They have to spend more time, again, focusing and on patient observation, rather than just going in and buying a bunch of flies and tying them on and frothing the water with them. I remember my days steelhead fishing, early steelhead fishing on the Pere Marquette River in Michigan back in the '70s, when they opened the river up to fishing all year. And we're fishing in the middle of the winter, and I'm trying little Prince Nymphs and little pheasant tail nymphs, size 16. We pumped the stomach of one of the steelhead, and it was full of little yellow stonefly nymphs. So we're fishing these small 14 and 16 flies, nymphs, and we're catching steelhead, and then you see these guys come by with these huge fluorescent orange, gaudy patterns, and they weren't doing a doggone thing.

So it's really cool when you figure out that simple flies, for the most part, work a whole lot better than these complex, gaudy things that really spook fish. And today, with catch and release, it's been proven that these fish may be caught once, but boy, the next time, it can be up to two weeks before they take a similar fly. And then when they get caught again, they're probably never going to take that flashy fly again. So fish are becoming educated, so to speak, by catch and release.

Soft hackles on bigger hooks for anadromous fish

CFS: Do you have tips or thoughts on those soft hackle flies for bigger hooks? I think maybe it was in Yvon's section, he mentioned an 8 or a 10 potentially being a size that he can take anadromous fish on. What are the considerations when you're sizing up, other than having the right size feather?

CM: Yeah, in some of those larger flies, it's hard to find really quality soft-hackle material that imitates what you're trying to imitate. We tie great big dragonfly nymphs for fishing the Firehole, fishing the Henry's Fork, and some of these other streams. And we really look for late-season Hungarian partridge, you know, with the larger feathers and the larger flues to tie those in. The larger aftershafts. We're always looking for those feathers.

We're kind of ghouls. We drive around and look for roadkill. I never met a roadkill bird I couldn't stop and skin real quickly.

We're kind of ghouls. We drive around and look for roadkill. I never met a roadkill bird I couldn't stop and skin real quickly. People wonder, "What the heck's that guy doing?" But I love to experiment with materials, and again, I always go back to pheasant and pheasant skins from wild birds. You don't want a tame bird. I gotta stress that right now. Everybody goes and buys a pheasant skin, and chances are they're buying a domestic bird that's been raised in a farm that's been pecked to death. You know, pheasants fight, particularly roosters. And they're fed an inferior diet, they're fed that mash or whatever. You get a wild bird that's eating insects, the feathers are much more vibrant, they're more oily, and they're usually larger flues. That's what you're looking for.

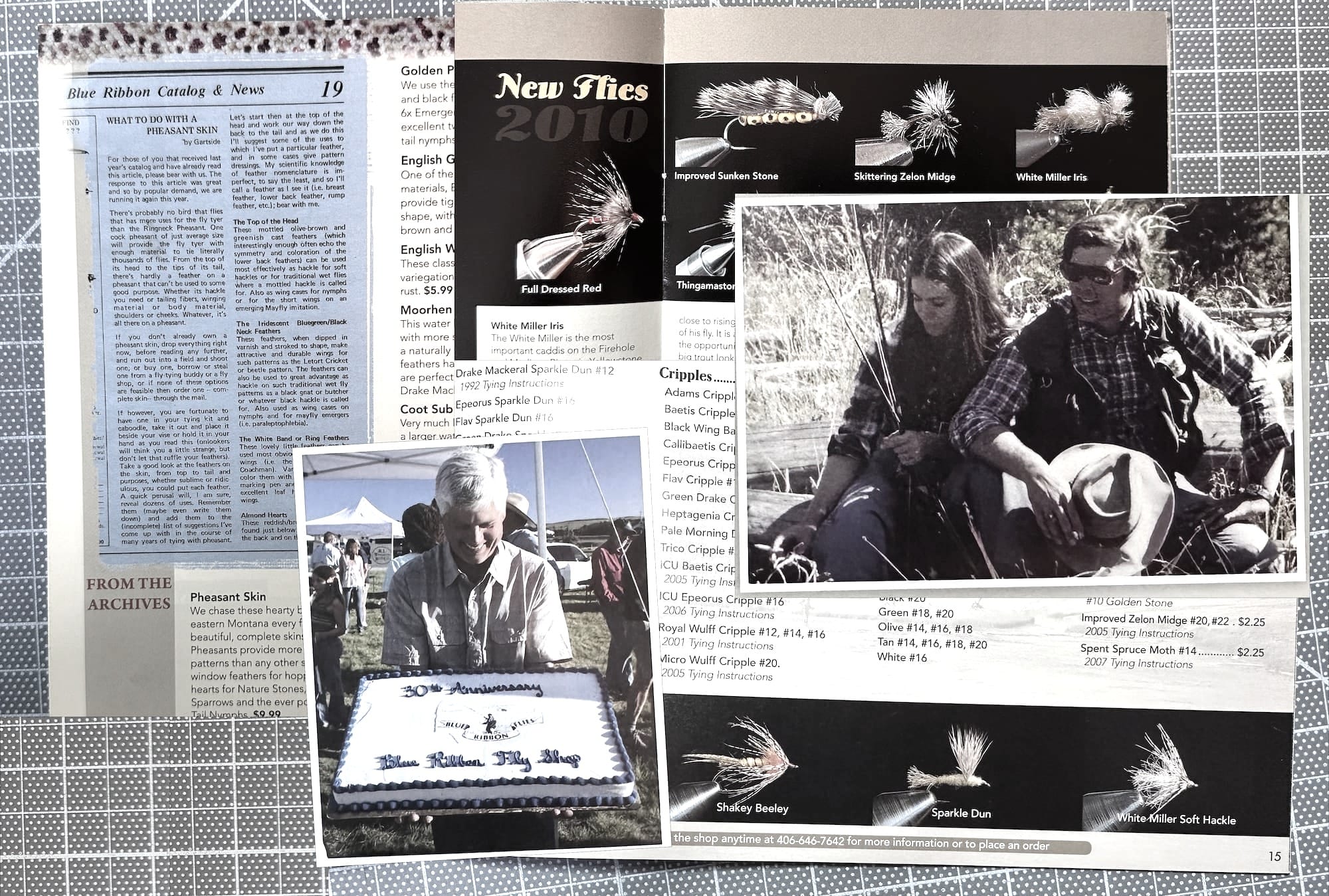

So, consequently, with the pheasant skin, you can find some of those larger soft-hackle materials, particularly the church window feathers on the back, just above the rump. And those are really quality feathers. Jack Gartside, my old friend from Boston who unfortunately passed away a few years ago, utilized the entire pheasant skin, every feather off it, to tie his soft hackle patterns with.

CFS: That's funny you mention Gartside, because I was cruising through the 2010 catalog, and there’s this sidebar from an even older catalog, "What to Do With Pheasant Skin" by Gartside. The more things change, the more they stay the same in a lot of ways.

He had a cigarette butt fly that imitated the filter of an Old Gold cigarette, and he would go down on the Gallatin and catch these great, big, wild rainbows.

CM: Totally, yup. Jack was a heck of an inventor, an innovator. He'd spend the summers in the basement of Blue Ribbon Flies, him and his cat, Toby. Jack would come up with these incredible fly patterns, mostly using pheasant skin. He loved pheasant, he used to use a lot of starling as well as Hungarian partridge. And some of the patterns he would come up with were just incredible, and very effective. He had a cigarette butt fly that imitated the filter of an Old Gold cigarette, and he would go down on the Gallatin and catch these great, big, wild rainbows and brown trout down by Big Sky, where the West Fork come in, and it was an incredibly effective fly pattern. Unfortunately, that's what led to his death, smoking Old Gold Straights. But he tied a fly that imitated those. But really what it imitated was the dicosmoecus caddis, the huge fall caddis that emerges on the Gallatin. There's some between the lakes, between Hebgen and Quake Lake, and those in the no-kill section, there’s larva and pupa this time of year, and catch some really, really big fish. And of course, the October caddis, that's what steelhead are feeding on up in British Columbia right now.

Collaboration and creative practice

CFS: You've been doing books and DVDs and videos for a really long time. How many books now have you been a part of?

CM: I believe this was the 10th. I've done books with John Juracek, of course, our first three books, Clayton Molinero, who used to work with us, Gary LaFontaine, and of course, Mauro and Yvon. This was our third book together. Simple Fly Fishing, then a revised edition of Simple Fly Fishing. The first one was geared more towards tenkara fishing, and the second one was with fly rod and reel.

CFS: And what was the process like? Are you guys getting better at this, as far as collaborators go, and working together?

CM: It's funny. We never even talk about it. We just sit down and go, "Okay, well, I'll do the dry fly, and Yvon will do the wet fly and soft hackle, and Mauro will do the nymphs," and away we go. And we just, you know, we just independently write it, and then put it all together, and Karla Olson, who does the editing for the most part, and John Dutton before her, they just go, "This is amazing. It's like you guys just sat down, all three of you, and just wrote the thing together." But we don't. We write it independently, and then we, you know, they just put it all together, and it kind of comes out. I'm very proud of what we've done from a writing standpoint.

What I like is when people get ahold of us and say, "You know, I wasn't a fly tier before, but you guys have really made me a fly tier, and made me into a very good fly tier, just by your simple fly patterns, and just, like, simple fly fishing." So many young people picked up the sport of fly fishing by tenkara. They said, "Oh God, it sounded so complicated, a reel, and a fly line, and a rod, and expensive." And you gave them an $80 tenkara rod, and they went out and caught fish, and it got them into fly fishing. That's what tickles me.

CFS: Yeah, it's funny, the sport is such an intersection of passions, right? You can sort of combine it with anything you care about, whether that's doing watercolors, or, you know, kayaking, or backpacking. There's something about the portability of tenkara, at least when we teach classes out here, so many people are like, "Oh, I'm a backpacker, I've always wanted to think about fly fishing," or "Oh, I love riding my bike in the woods, my mountain bike, how can I incorporate fly fishing into that?" And in a lot of these cases, tenkara is the most immediate answer, because it's portable, it's simple, doesn't—it's not expensive, so yeah, it feels like it really falls at the intersection of a lot of these other things.

One of our biggest customers, in terms of purchasing tenkara rods, were motorcycle gangs.

CM: Totally, and one of our biggest customers, in terms of purchasing tenkara rods, were motorcycle gangs. Every year they’d be on their way to Sturgis, to the big motorcycle rally, and they'd pull in and they'd buy skunk tails to hang off their helmets. And all of a sudden, one of them picks up a tenkara rod and goes, what is this? You know, this little bitty—and they all said, "God, we love to fish." And we got them into tenkara fishing.

And I love to tell the story of one of the meanest bikers I ever met in my life, who had been in prison for murdering a fellow biker with a chain. And over time, I got him tenkara fishing. But he never liked me. He'd always come in and scowl, and he had that long hair and a big beard, and he was a huge man. And about ten years after I last had seen him, in walks into Blue Ribbon Flies walks this little bitty old man, all crippled up, with a long, greasy ponytail, and it was him. I said, "Tiny!" He goes, "You remember me?" I said, "How could I forget you? You're as mean a person as I ever met in my life." Anyway, we shook hands, and we went tenkara fishing that afternoon.

Get involved!

It's time to get your fly-tying fix sorted for this winter.

Ready to get involved? Join us for a virtual discussion of the book on Sunday, November 2nd, and get a chance to win a giveaway copy.

PDX locals can join CFS pals and class alums at Friday night in-person tying hangs in NE Portland on November 14 and 21st.

The creative process and writing practice

CFS: I was looking at Fly Patterns of Yellowstone the other day, and in the acknowledgement, you thank Jackie for doing all the typing. What's changed in your personal writing process since you started? Do you like writing?

CM: Yeah, it just came kind of naturally to me, I guess. You know, I used to write a lot of police reports. I was a cop for 14 years, so I did a lot of writing when I was a police officer. I really enjoy writing, but what's really changed, of course, is the computer. I used to longhand every doggone thing that I wrote, including our first and second books, I just longhand wrote it—wrote it out longhand on a legal pad. Computers have really enhanced that and made it a whole lot simpler. I am totally helpless when it comes to technology. I'm a Luddite, and so is Chouinard. We don't really even know how to turn on one of these god-awful things. [holds up iPhone].

I said, "Are you doing okay?" And he said, "I think I'm having a stroke!"

CM: Yvon and I went fishing in the park one day. I picked him up in his place in Moose, and we're driving into the south entrance of the park. And he said something to me, and I looked at him, and I said, "Are you doing okay?" And he said, "I think I'm having a stroke!" I went, "Jesus Christ!" So I pull over to the side of the road, and I said, "Tell me your symptoms." He said, "My whole right side is numb and trembling."

So I said, "Can you walk?" He gets out, and he's kind of walking in circles. And I reach in his fishing pants, and he goes, "What the hell's that?" I said, "I think it's a cell phone." He goes, "I don't own a cell phone. What are we gonna do?" So we threw it in the back of the truck, and we went fishing. His wife had put a cell phone in his pocket in case he had a health issue, and neither one of us knew how to answer it.

Fly fishing filmmaking evolution

CFS: Like, similar to the book world, there's the fly fishing film world. You've obviously done films for a long time, how has that process changed? I remember seeing Bob Jacklin shooting a DVD between the lakes, where there's that really high bank over by upstream from the Campfire Lodge, and they had multiple cameras up on the banks—it seemed like a really big production. Has that gotten easier, making video around some of this stuff, or is it just different?

CM: They shoot great video now on these god-awful things. A good friend of mine, Forrest Mankins, from Whitefish, a really talented photographer and videographer, he just runs around now with his little cell phone, or a much smaller camera. I remember the batteries, you know, guys had to wear belts with batteries on them and stumble along. We filmed the David Letterman show from our fly shop here on the Madison years ago, when he had his two Bangladeshi guys, Sirajul and Mujibur, and we had a huge satellite truck and these monster cameras lugging them around, and now it's so simple now compared to what it used to be. I might even be able to run one of those cameras now.

The future, activism, and advocacy

CFS: Let's talk about the future a little bit. What are some things in fly tying that you're seeing right now that have changed?

CM: One thing that's changed big time in the last few years is the activism and advocacy that's been developed by people getting into the sport. When you get someone tying flies, and they're fishing flies, and they understand wild trout and clean air and clean water and wild places, they become an activist and an advocate for those places that we all cherish and love. So, that's a real benefit, I think, to the future of our sport.

People see how climate change can affect these areas that we love, from whether it's clean water, clean air, all of the above. And young people really especially—hey just jump in with both feet and become better advocates, activists to protect and preserve our sport.

CFS: In the greater Madison Valley, in the greater Yellowstone world, you and your colleagues and other compatriots have had a really tremendous impact. Not only with things like 1% For the Planet that's changed the outdoor industry, but even more localized matters. I remember when whirling disease was a big issue. And it felt almost apocalyptic from afar. And the community involved worked together and eventually a solution was found. What advice would you give people who might not feel like there's a lot of headway being made in some of these efforts around conservation or public access, or there's always sort of things—there are always sort of new battles that are coming along. Having seen some of these wins, what does it mean to keep working when it doesn't always feel like there's a win in sight?

CM: The classic example was $3 Bridge, and most people are familiar with that. I was really pleased that, and honored, that our shop led the way to protect and preserve $3 Bridge, four miles of the Madison River. And at that time, you know, subdivision was, and still is, one of the biggest issues. And we potentially could have lost about four miles of public access to the Madison River, and probably the most iconic stretches of the Madison River, the most productive and scenic.

I'll never forget, we approached the rancher and said, "Hey, we'd like to buy this stretch, if you ever decide to sell it. And he said, "I'll let you know." Well, two years later, he called and he said, "Hey, we've got some health issues amongst the owners, we need to sell the farm here."

And it was a 5,600-acre piece, again, four miles of the Madison River. People thought we were nuts. They said, "You can't do this." Well, we started a project to buy it, to raise $5.6 million, $1,000 an acre, to buy it. And we were struggling. We bought an option to buy it for a quarter of a million, we had raised another quarter of a million, and we're struggling raising that money. But all of a sudden, a guy walked in the shop and said, "Will you explain to me what you're trying to do?" And we explained it to him. He said, "How about this? I'll buy the whole property. I'll do a conservation easement to never build one building on it. We'll leave it open to hunting and fishing forever." I said, "I could just kiss you on the forehead."

Where I'm going with that is, that served as a model for other projects that we did, whether it was the Sun Ranch easement, the Olive Ranch easement, the Granger Ranch easement, all these easements, and we have the Madison River Valley now, about 60% protected by conservation easements. In a conservation easement, of course, they sell their development rights, so it'll look just exactly the way it looks right now. And much of that doesn't guarantee public access, but much of that is open to the public for fishing and hunting. And it all started with this one conservation project, and young people were really receptive to that, and picked up the ball, and really helped us greatly in accomplishing that project. Everybody said, "You can't do it," and we got it done. And with that, so many of these young people heard that. "You can't, you can't, you can't," and they started with, "Yeah. Yeah we can." And they've continued that process.

CFS: So keeping that momentum up, building on the small wins.

CM: Eventually, they will lead to much larger wins. We had another project here just a couple years ago down below from Palisades down all the way to McAtee along the river, there was eight miles of BLM property that you could not access unless you had a boat. Well, we worked with the owner of that, it was a friend of mine. We said, "Hey, would you be willing to sell us that?" And it fronted the highway, Highway 287, for public access, so they could get walking access to down to that stretch of river that had never been accessible before for the walking angler. And he said, "God," he said, "I never thought of that. Nobody ever approached me. I've just used it for grazing." Well, I said, "Well, we'll allow grazing, but we just don't want to see it developed and posted when we get it done." We got a federal land appraisal. We went to the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Our U.S. Senator at the time saw the value in that, and brought that money home to Montana, and we got that project done. And again, people said, "Oh, you'll never get access to that." Well, we opened up eight miles additional access on the Madison River, just by going and talking to somebody

CFS: What's inspiring you right now?

These young people are gonna save this world.

CM: Again, young people. If you can't get inspired by the energy that they have in trying to fight climate change, and trying to keep public access, and gain more public access to public water, if that doesn't fire you up, nothing does, because these young people are gonna save this world.

CFS: What are you working on next, other than this season's elk?

CM: I'm after my 47th mature bull in 47 years. I've gone 46 for 46, and I bought a license the other day, so I guess I'm gonna go after another elk. I'd like to get to 50, but I'd be 80 years old then, I don't know if I can do it, but I'm gonna give her a shot. I'll be out there this Saturday, they forecast rain and snow and 30 mile an hour winds. I'll be out there at 4 a.m. looking for a bull elk.

And I'm also working on a memoir of my police chief years. My good friend, Tom Brokaw, a lot of you will remember from NBC News, encouraged me, and so has Yvon and Melinda Chouinard and my wife to write those stories, because they're full of all kinds of laughs and giggles. And tears, too, blood, sweat, and tears, but anyway, I'm working on that, and I'm over 100,000 words in on that project. I've been working on it for years, and then this Pheasant Tail book and the other Simple Fly Fishing books kind of got in the way, but we got those done, so now I'm really working hard on that. And some conservation projects we're still working on here. More on that later.

Don't wait! Get your copy of Pheasant Tail Simplicity today:

Paid member exclusive: Watch the whole conversation

Logged-in paid members can sit in on my unedited conversation with Craig.